The Body Motion Problem (BMP) is a fundamental challenge in robotics, addressing how robots can compute goal-directed, context-sensitive motions to achieve desired outcomes while adapting to real-world constraints. Beyond simple motion generation, BMP requires robots to interpret task goals, infer causal relationships, predict consequences, and dynamically adjust their actions. This makes BMP computationally complex, necessitating a structured approach to problem-solving. To make it tractable, BMP is decomposed into three interdependent subproblems: (1) Identifying Physical Changes required to fulfill a task request, (2) Determining Actions and Forces needed to achieve these changes, and (3) Generating Forces Through Body Motions that execute the necessary movements reliably. By structuring BMP in this way, researchers can systematically analyze and develop solutions that generalize across diverse tasks and environments.

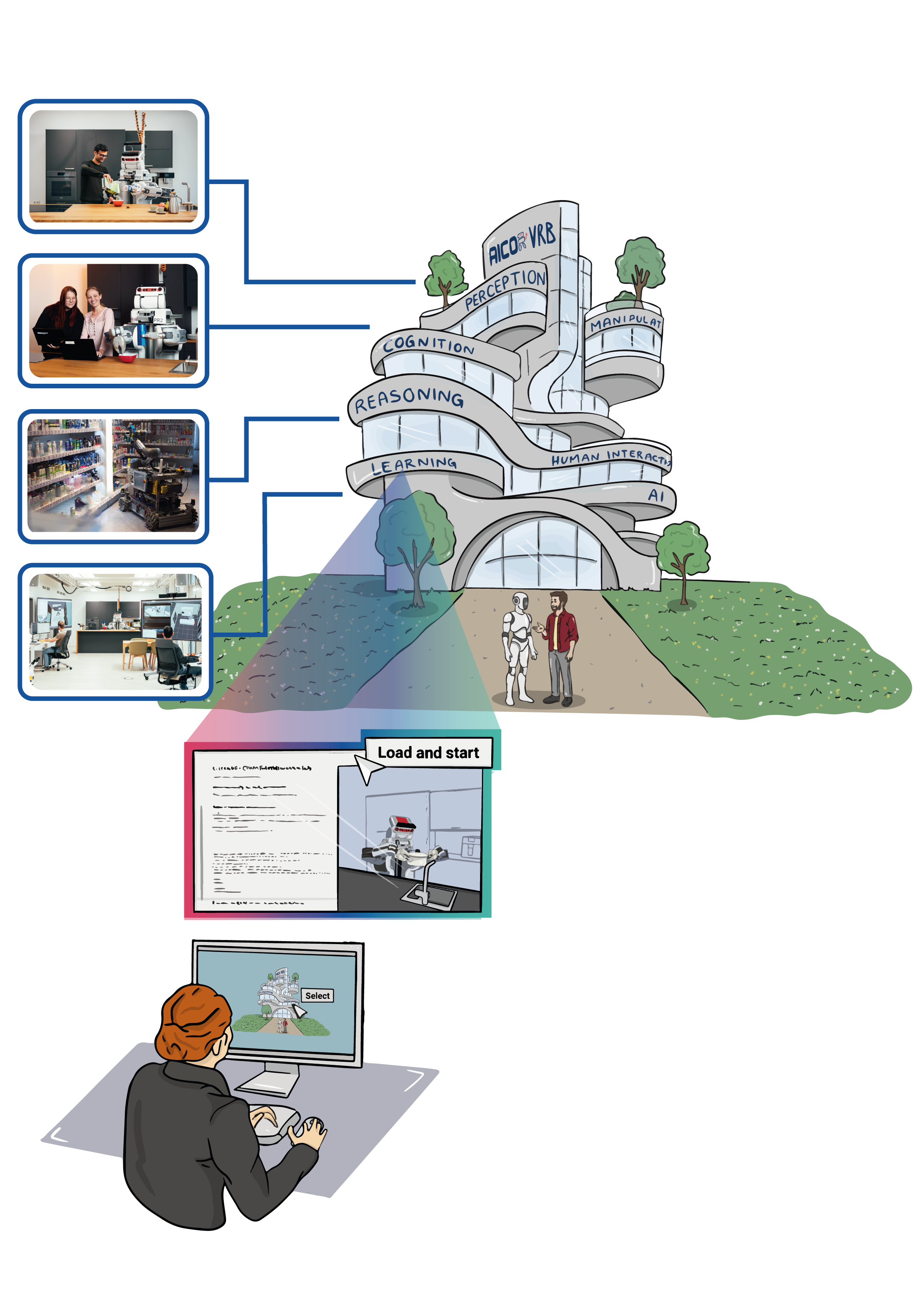

Interactive Examples

Description

The decomposition of the BMP leads to the formalization of the Law of Task-Achieving Body Motion, which defines the conditions under which robots can reliably complete tasks while adapting to changing contexts. It provides a structured approach for robots to interpret, plan, and execute context-sensitive actions. $$ \forall R, E, T, G, M [TaskRequest(T, G) \land Causes(M, G, E) \land CanPerform(R, M) ] $$ $$ \rightarrow CanAchieve(R, T, E, M) $$

Where:

- TaskRequest(T, G): The goal ( G ) defines the desired environmental change required to complete task ( T ).

- Causes(M, G, E): Motion ( M ), when executed in environment ( E ), reliably produces ( G ).

- CanPerform(R, M): Robot ( R ) has the necessary physical and computational capabilities to perform ( M ).

Consider the task of opening a refrigerator—a common but computationally complex action. Using the BMP formalization, this task is decomposed into three subproblems: understanding the task goal, determining the necessary actions, and executing the required movements. Each subproblem can be approached with different computational methods depending on the domain and requirements.

1. Identifying the Task Goal (TaskRequest(T, G))

The robot must first determine that the fridge door needs to transition from a closed to an open state. In this case, the task goal (G) is identified using logical reasoning—the robot infers from a structured knowledge base that pulling the handle achieves this transition.

However, in other domains, such as human-robot interaction or noisy environments, a probabilistic reasoning approach (e.g., Bayesian inference or learning-based methods) might be more effective. For example, if the task were to determine whether a user wants a drink, probabilistic models could infer intent from gaze tracking, gestures, or speech recognition rather than relying solely on logical deduction.

2. Determining Necessary Actions (Causes(M, G, E))

After identifying the goal, the robot must compute a motion (M) that reliably achieves the state change in the given environment (E). For opening the fridge, this involves leveraging a kinematic model of the fridge door, considering factors like hinge constraints, handle position, and required torque. This allows the robot to compute the force and trajectory needed to pull the door open while respecting mechanical constraints.

However, in a different domain, such as pouring a liquid, a kinematic model alone would be insufficient. Instead, the robot would need to use a physics-based fluid dynamics model to predict how the liquid will flow under gravity and how tilting the container at different angles affects the pouring rate. This highlights how different problem domains require different physics models to compute the correct motion that leads to the desired state change.

3. Executing the Motion (CanPerform(R, M))

Finally, the robot must determine how to physically execute the motion using its own body. This involves kinematic motion planning based on the robot’s URDF (Unified Robot Description Format) model, ensuring that its arm and gripper move in a way that allows secure grasping, controlled force application, and smooth trajectory execution. This ensures that the fridge is opened without excessive force or unintended side effects.